For decades, George Perry’s world-record bass suffered from a case of mistaken identity.

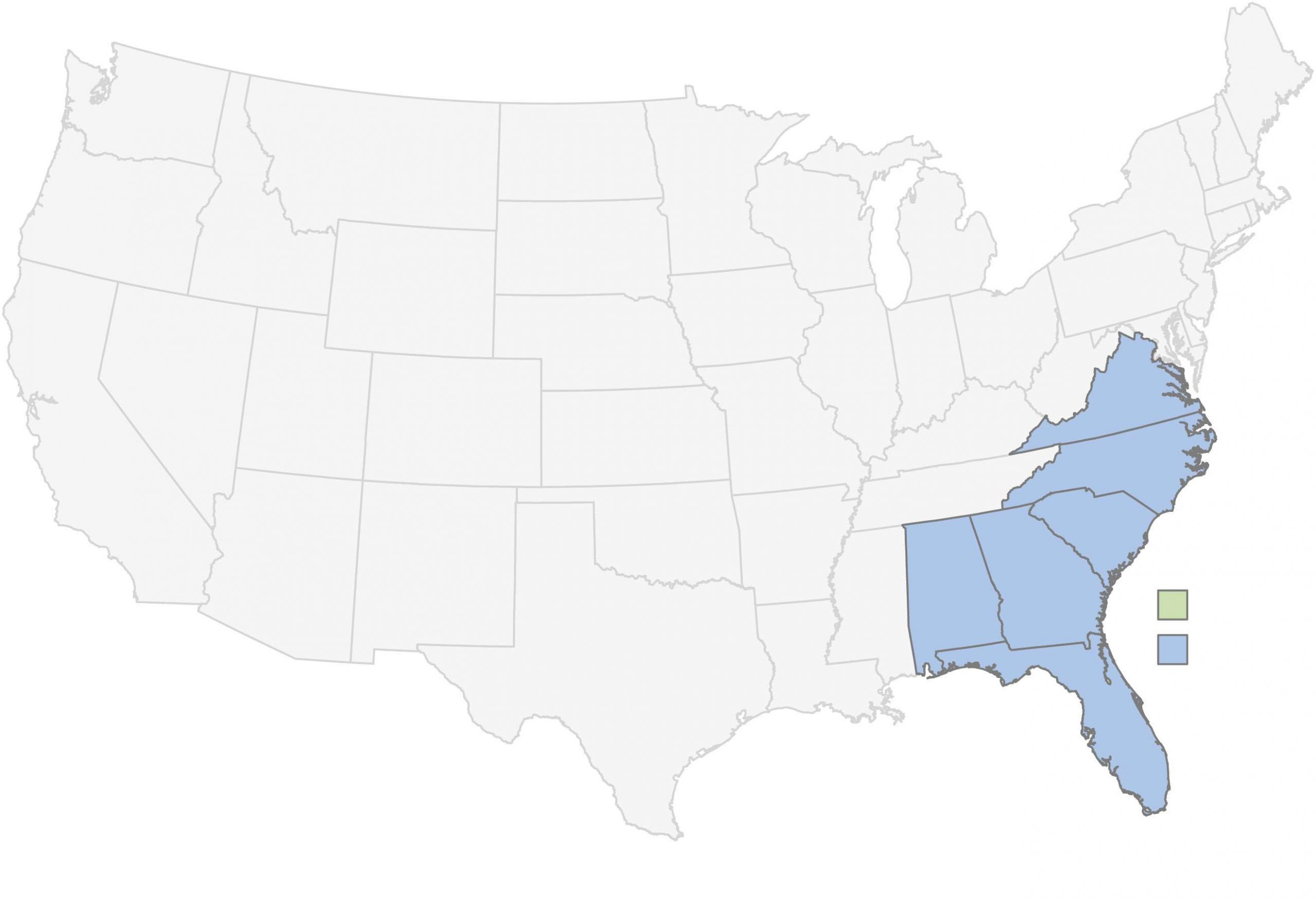

That revelation is but a part of a larger discovery by Auburn scientists that likely will have implications for the way bass fisheries are managed and stocked from Arkansas to Virginia.

Of course, we never will know the genetic ancestry of that 22-pound, 4-ounce fish that Perry caught in 1932 in Lake Montgomery, an oxbow near Georgia’s Ocmulgee River. But until recently, the assumption was that the bass was a Northern-strain largemouth bass (now classified simply as a “largemouth bass”) or, at best, a Northern/Florida bass intergrade (a cross between two subspecies).

That calculation was based on the belief that the natural range of the Florida bass is limited to the peninsular portion of the Sunshine State. That no longer is the case for the fish that generally grows faster and larger than the Northern subspecies, according to Eric Peatman, professor of fisheries at Auburn and head of the Southeastern Fish Genetics Cooperative.

“We provide genetics services for states, private pond management companies, hatcheries, etc., allowing them to test genetics of black bass populations,” he said. “In the course of running tens of thousands of samples from across the region, we’ve been able to establish some geographic distribution patterns that cut against the widely accepted wisdom about largemouth bass.

“Through analysis of genetic markers we’ve more recently discovered, it’s most likely that Perry’s record fish was a Florida bass,” he continued. “In those coastal rivers, pure Florida bass dominate. In the St. Marys River of Georgia, for example, it’s essentially 100% Florida bass.”

What’s more, Florida genes dominate all the way up to Georgia’s Fall Line, which runs roughly from Columbus to Augusta. They also extend all the way up into coastal regions of North Carolina and probably into Virginia. But Peatman cautioned that more data is needed to confirm the latter.

Additionally, what the biologist believes are natural intergrade populations (prestocking) cover “all of Alabama, much of Georgia above the Fall Line, the majority of Tennessee populations, most of North Carolina and some of Arkansas.”

This differs considerably from the narrative originated by fisheries scientists Reeve Bailey and Carl Hubbs during the 1940s that intergrades were native mostly only to Georgia and the Florida Panhandle and the subsequent belief that their presence elsewhere was only the result of Florida bass stocking.

“From our findings and Tom Near’s [at Yale], Bailey and Hubbs got pretty much all of the historic Florida/Northern/intergrade bass map wrong,” Peatman said.

Although the totality of this new expanded range will come as news to many, resource managers in Southeastern states already knew some of their fisheries contained Florida genes that they couldn’t explain.

“We’re finding at least a low level of Florida genes in lakes where we haven’t stocked,” said Jeff Buckingham, Black Bass Program biologist for Arkansas. “We don’t know how they got there. Maybe anglers moved fish. But we just don’t know.”

Arkansas spawns 2 million Florida fry annually at two hatcheries and stocks them in 15 lakes, mostly in the southern part of the state, with Millwood Lake being a prime recipient. The goal is to enhance the gene pool and consequently grow bigger bass for anglers as those introduced fish breed with native largemouth.

Adding intergrades

In North Carolina, biologists are in the third year of a population survey, sending fin clip samples to Auburn for analysis.

“What we are seeing mostly are a mixture of largemouth and Floridas,” said Lawrence Dorsey, North Carolina’s Piedmont fisheries research coordinator. “As we go farther toward the coast, we see more Florida influence. As we go west, that wanes and we see more Northern-dominant hybrids.

“We’re seeing no pure Florida or pure Northern populations,” he added. “A few fisheries on the coast are heavily influenced by Floridas. But most of our populations are hybrids, with multiple generations of crossing.”

Unlike Arkansas, North Carolina is not stocking pure Floridas and it’s not stocking multiple fisheries. For now, at least, its focus is only on Lake Norman, with a five-year plan to stock 130,000 F1 fish (first generation Florida/Northern intergrades) annually, or about four per acre.

“We’re not stocking [pure] Floridas because the genes already are there,” Dorsey said. “Our fish are FXs, which means they’re anywhere from second to hundredth generation. Stocking pure Floridas in Norman wouldn’t give us hybrid vigor like it did in Tennessee [in Chickamauga Lake].”

Also, North Carolina’s goal is not about enhancing the fishery. “The stockings may produce larger bass for anglers, but that will take some evaluation,” Dorsey said.

The focus is on sustaining the largemouth population against a growing population of more aggressive Alabama bass, likely introduced illegally by anglers.

“There are a lot of Alabama bass there,” the biologist said. “They’re also showing up in Lake Gaston and on the Roanoke River chain. They’re in Virginia now, and they’re quickly gaining ground. Alabama bass are going to shape our management of largemouth and smallmouth bass for the foreseeable future.”

Plenty of F1 largemouth/Florida intergrades (also known as “tiger bass”) are also in Virginia waters, courtesy of the state stocking Smith Mountain and Claytor Lake, as well as lakes Anna and Chesdin.

“What we’ve found is that our largemouth bass populations are made up of fish with Northern and Florida genetic traits,” said Scott Smith, regional fisheries manager. “We typically see anywhere from 40% to 60% Florida genes. All our populations appear to be mixed.

“By stocking F1 fish, we are not introducing any new genetic material, and we aren’t doing this in an attempt to change the genetic composition of the populations.”

Rather, the intent is to provide anglers directly with bass that grow faster and larger because of the hybrid vigor that occurs when subspecies are bred.

In Georgia, meanwhile, where the presence of Florida genes ranges from 100% in the southeast to more than 50% in the northwest, fisheries managers use a selective breeding program in hopes of growing bigger bass for anglers. As brood stock, they use bass taken from systems where fish typically grow faster and larger than average.

Not surprisingly, some of those bass come from waters near the site of George Perry’s world-record catch.

“Montgomery Lake isn’t much of a lake anymore,” said Georgia fisheries chief Scott Robinson. “It’s naturally filled in with sediment and aquatic plants over the years. But we have sampled quite a few bass from around that area. We see 80% to 90% Florida genes in fish in that area.”

As varied as strategies and goals already are for stocking Florida bass, and especially intergrades, they probably will become even more so with this new knowledge of the expanded range. Ideally, this will result in better results for anglers, as well as a reduction in waste of time, money and effort for state agencies. For example, fisheries managers now have a better idea of where not to stock pure Floridas with the hope of boosting the gene pool to grow bigger bass. That typically won’t happen in a lake that already has an intergrade population.

On the flip side, if climate and habitat are conducive, putting Floridas into a lake inhabited solely by pure Northern largemouth can result in hybrid vigor from the crossing of the two subspecies and bigger bass, which was the case for fisheries in Texas, Oklahoma and California.

“These findings have implications for anglers and state fisheries biologists,” Peatman said. “If Florida bass are native to a larger region than peninsular Florida, then our view on transport and stocking may need to change.

“What’s the difference in performance in Tennessee between a Florida bass from central Florida and a Florida bass from coastal North Carolina? We don’t know, but it would be interesting to examine.”

Steve Sammons, a black bass expert and associate of Peatman’s at Auburn, added this caution: “I am unsure if anyone has ever truly nailed down concrete reasons behind success or failure of these programs, other than the obvious winter temperature limitation.”

Sammons cited research at Lake Guntersville that found Florida genes to be common but almost nonexistent downstream in Wheeler Lake, “despite similar stocking history and the connection between these water bodies.

“Believe me, if agencies could say with certainty that this will or will not work, we’d all be a lot better off. But it is still somewhat of a crapshoot.”

The delta variant

As Eric Peatman and his staff at Auburn charted an expanded range for Florida bass and Florida/largemouth intergrades, they also determined that a third variant exists: the Delta bass.

“Basically, it’s a third lineage that appears to have radiated out of the Mobile River Delta and established below the Fall Line in Alabama,” Peatman said.

“It also appears to have spilled over the Fall Line during high-water times, [glacial melting, for example], and mixed in different proportions with Northern and Florida bass to make complex hybrids.

“The influence of Delta bass is also seen in Tennessee, Georgia and North Carolina populations we’ve surveyed,” he said, adding that Mississippi populations have not yet been examined.

As an adult, the estuarine Delta bass generally is smaller than its counterparts in inland populations but with “larger relative weight,” meaning it’s fat.

No Florida bass here

Many anglers continue to mistakenly believe that growing bigger bass simply is a matter of adding Florida genes to the population, even in lakes where habitat and forage are not appropriate and in states where climate is too harsh.

That’s especially the case in Kentucky, where envious fishermen see the trophy bass fishery developed at Chickamauga Lake in adjacent Tennessee. The fact that its neighbor also partnered with Henry County to stock 300,000 Florida bass fingerlings in Kentucky Lake earlier this year didn’t help either, although results won’t be known for years.

In response to a request to stock Florida bass in nearby Lake Barkley, the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources produced a paper titled “Why Not Stock Florida Bass in Kentucky.” Here’s an excerpt:

“The stocking of Florida bass in other states can be a good idea, and if we were just a little further south, it might be something to consider. However, we are too far on the edge of uncertainty due to our longer cold season.

“The risk is too great for us to take a chance on Florida-strain stockings. Our Northern-strain largemouth evolved over a long period of time under Kentucky’s climate. They are better suited for it. By stocking the Florida-strain largemouth, we would be mixing in genes that are potentially inferior for Kentucky’s climate.

“The mixing would result from the Florida strain spawning with the Northern strain [creating a hybrid of the two strains] and would dilute the gene pool that has evolved in Kentucky.”

Agencies in other states on the northern border of the Florida intergrade zone are often pressured by anglers to stock Florida bass or F1 hybrids but don’t do so because of the same reason given by Kentucky: They have pure Northern largemouth bass populations that are adapted to the state’s climate and feel that introducing the non-native strains will ultimately do more harm than good.