David Fritts knows well the fish-attracting charms of green pumpkin baits, but the Elite pro from Lexington, N.C., also values the spider-repelling power of a certain green gourd he grows on his 120-acre farm.

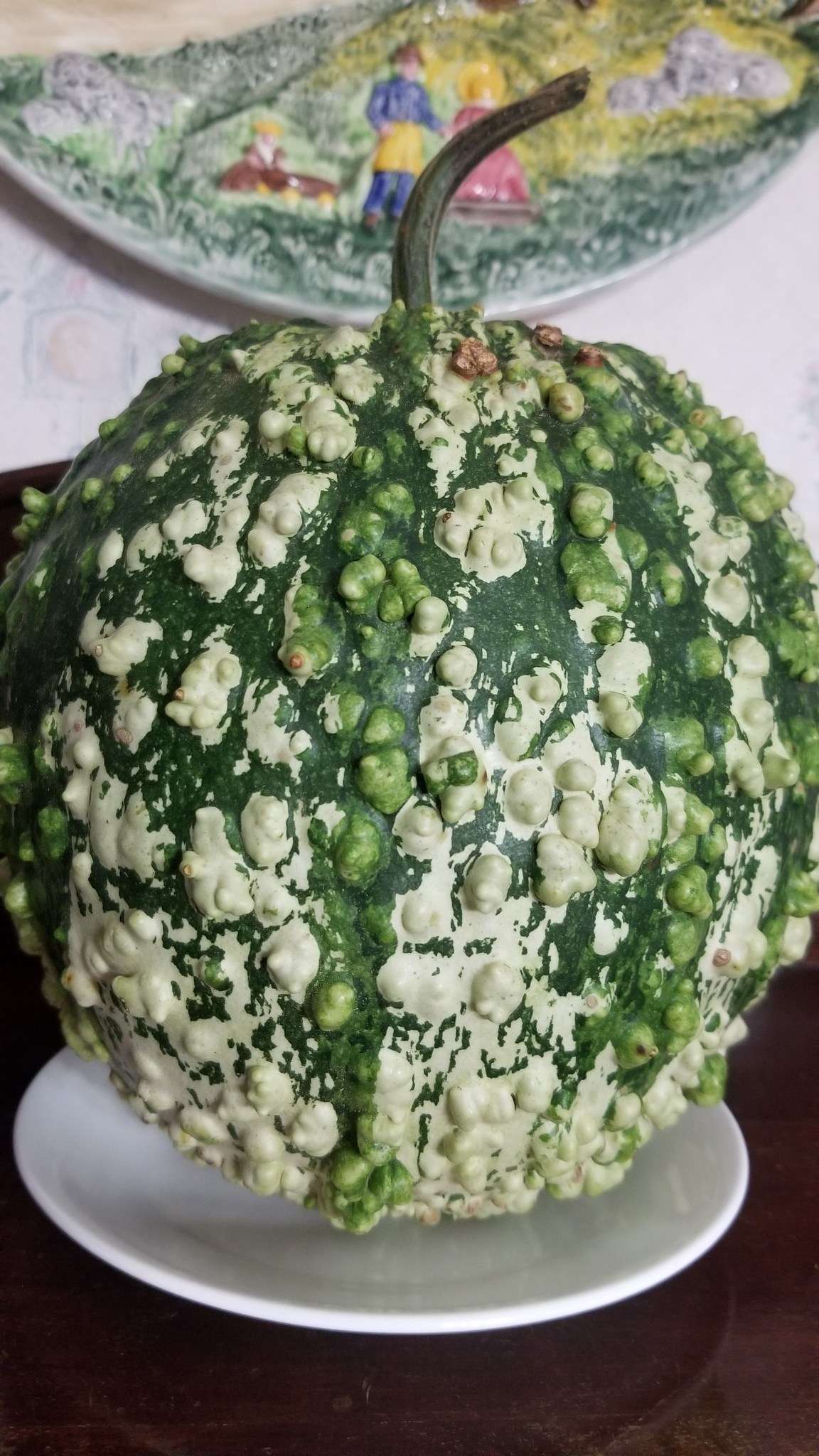

Yep, the “spider gourd” is said to keep creepy arachnids out of your home, and the fact that he never sees a single eight-legged intruder in this particular section of his field seems to validate the premise.

If you didn’t know, the 1993 Bassmaster Classic champion, recently inducted into the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame (class of 2019), spends most of his non-fishing hours running the family-owned and operated David and Tom Fritts Produce, founded with his late father. Spider gourds are only one element of this Central North Carolina operation, but they’re a fine representative of the farm’s noteworthy nature.

“I don’t know how true (the repellant reputation) is, but we’ve never had a spider in a gourd field,” Fritts said. “Everyone here swore it kept spiders out, so my mom started calling it the ‘spider gourd.’ When you have pumpkin fields, cantaloupe fields — especially watermelon fields — they’re full of spiders.

“When you plant spider gourds, you never see a spider; I mean never. I’m sure it’s not going to kill a spider if he walks into the same room with a spider gourd, but they don’t like it. I raise 1,000 to 2,000 of them a year and we sell them about as fast as we can pick them.”

Roughly the size of a cantaloupe and typically dressed with dark green, light green and white exteriors, spider gourds join several other ornamental gourds (including decorative pumpkins) as the largest segment of Fritts’ production.

“They’re not a food item in the United States; they’re more for decor,” Fritts said. People make birdhouses (and other craft items) out of them. One of the prettiest things is to paint them silver or gold and put them on your Christmas tree; they’re light as a feather when they dry out.”

The crops

With spider gourds occupying about an acre of his farm, for the past 25 years, Fritts has also raised sweet corn, Indian corn, cantaloupes, watermelons and tomatoes — along with an international tapestry of colorful gourds originating as far away as New Zealand. The latter is his mainstay, and if you think it’s just a matter of planting seeds and picking what the vine yields, think again.

For one thing, gourds (particularly pumpkins) require biweekly nocturnal spraying to prevent various windblown crop disease spores. Can’t spray during daylight hours, or you risk killing the bees needed for pollination. And if a tropical weather system approaches the Carolina coast, big winds can carry devastation into farmlands.

“I’ve had a whole field wiped out overnight because of disease,” Fritts said. “All that tropical air has a lot of spores in it and coming off the coast, it has very high humidity that promotes disease. In a year with three or four tropical storms, we have lost over half our pumpkin crop.”

The process

Once picked, ornamentals destined for tabletops, centerpieces and craft stores throughout the Southeast, require lots of TLC. After thorough washing, each one gets a disinfectant dip to eliminate rot risk and a clear spray-on sealant that makes each gourd last from its fall prime time through spring.

Fritts said the results merit the effort, as ornamental produce typically draws a more discerning clientele than purely food crops. For Fritts’ gourds, the best of which may fetch $40 to $70 each, the visuals must be tighter than a Palomar knot and, like architecture, form follows function.

Specifically, ornamental pumpkins and other gourds need flat bottoms for proper positioning. Also, dipper gourds (long, thin necks with bulbous ends used for ladles or dippers) that develop curved, twisted, even knotted necks bring top dollar for their character and aesthetic appeal.

Achieving both consistency where it counts and novelty, where it’s possible, is no more random than a Bassmaster Classic victory. While prudently positioning dipper gourds allows for optimal neck development, strategically planting adjacently species gives the bees creative license to cross-pollinate here and there, often with spectacular results.

The rewards

No doubt pumpkins and other gourds demand much effort and attention, but Fritts said he never tires of strolling fields of ripe, colorful beauties; finding a truly unusual color pattern or watching a gargantuan pumpkin — like his nearly 600-pound personal best — reach maturity.

He’s won plenty of county fair ribbons and compliments are frequent. But, while he doesn’t do it for the recognition, Fritts indulges in a moment of satisfaction while recalling a particularly gratifying honor.

“We’ve had people buy pumpkins from us at the Greensboro Farmers Market so they could take pictures and make replicas to sell at Walmart and other stores,” he said. “That’s pretty special to have someone tell you they’re going to make porcelain or plastic replicas of your pumpkin. To come to you and use your pumpkins — that tells you something.

“Also, we’ve had people spend an hour in our booth and say, ‘We’ve never seen anything like this.’ It’s pretty rewarding what people say — even though they don’t have a clue what all goes into it.”

Meaning and motivation

Now, if you’re “green” with envy (sorry, it was right there), Fritts quickly points out the realities of small farming.

“You can’t hardly make a living at it because there’s always something (like rising fertilizer costs) that offsets your chance of making money farming,” he said. “Maybe if you had 5,000 acres and you raised field crops, there might be a little more money in it, but there is not very much money in farming. I fish (professionally) so I can farm.

“There’s something about raising (crops) from a seed that gets in your blood; there’s a certain pride to it. It’s a necessity; the world needs farmers.”

So, why does he do it?

“There’s a lot of pride in it; we try to be the best we can be, just like when we’re out there fishing,” Fritts said. “A lot of people think that just getting by is okay, but we want to do a lot better than just getting by with normal pumpkins and gourds.”

Doing so demands dedication; no shortcuts to success.

“To be the best you can be, it takes a lot of hard work in both fishing and farming,” Fritts said. “When you live on a farm, you learn hard work. It’s not getting up at 8 o’clock in the morning and quitting at 5; it’s daylight to dark and half the night. It’s the same way in fishing; putting in your time on the water and working hard.

“I guess knowing how to make a crop produce is like the know-how of making fish bite. Whatever I do, farming, fishing or baking — I love to bake — I try to do the best I can do and actually a seed above that.”

So, whether he’s competing on the Bassmaster Elite Series or tending to his crops, David Fritts is all-in. He knows what it takes, he knows the value of that significant commitment and he knows there’s no other way.

The proof is in the…produce.